When Pricing Follows

What Happens When SaaS Pricing Follows, Instead of Leads

In a recent role, we priced our SaaS product with a flat annual enterprise fee, loosely based on customer profiles. It seemed strategic, simple, scalable, and benchmarked against a familiar competitor on paper. In reality, it worked for no one. For context, we were approaching the EMEA market where we had little to no existing clients, and unlike a GTM motion in the US, not all regions can be treated the same. There are differences in pricing sensitivities, willingness to pay, and expectation of performance of Saas tools for financial services. These differences were most prevalent in the smaller to mid tier customers.

Too Big or Too Small Never Just Right

Our pricing structure was too large for smaller players, yet not complex or flexible enough for larger ones. It encouraged client usage, but with no pricing variable tied to outcomes or scale. There was no mutual growth, no incentive alignment, or opportunity for expansion. Just a one-size-fits-all model. The product's basic components were the same for all enterprises, the only difference being that large customers would collect and report on larger data sets, generally requiring more complex functions to generate and segment their Internal Rate of Return.

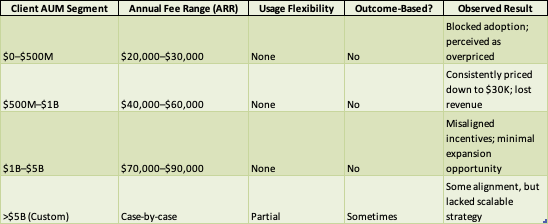

This “one-size-fits-none” approach looked clean on paper, but didn’t reflect the range of client needs or the value we were delivering. Here’s how our flat-fee ARR model played out across AUM segments:

Flat-Fee ARR Pricing Table

We anchored our pricing to a legacy competitor, not because it fit our product, but because it was familiar. The irony? We were trying to replace that legacy, while pricing like it.. But the irony was hard to ignore: we were trying to replace this legacy provider while mimicking their pricing. Our product was differentiated, but our pricing didn’t reflect that. It lacked originality, clarity, and most importantly, strategy.

Pricing That Didn’t Travel

When we entered new markets, we brought the same pricing structure, despite having no brand equity, no client references, and no local validation. It failed to land. Prospects saw a high price and no evidence to justify it. We expected legacy-level pricing power without the credibility to back it up. Now, the US-based team was doing their job selling the product, at least holding their own compared to the competition, while the buyers from international markets had a much different view of either what they expected to pay/or what features should be table stakes.

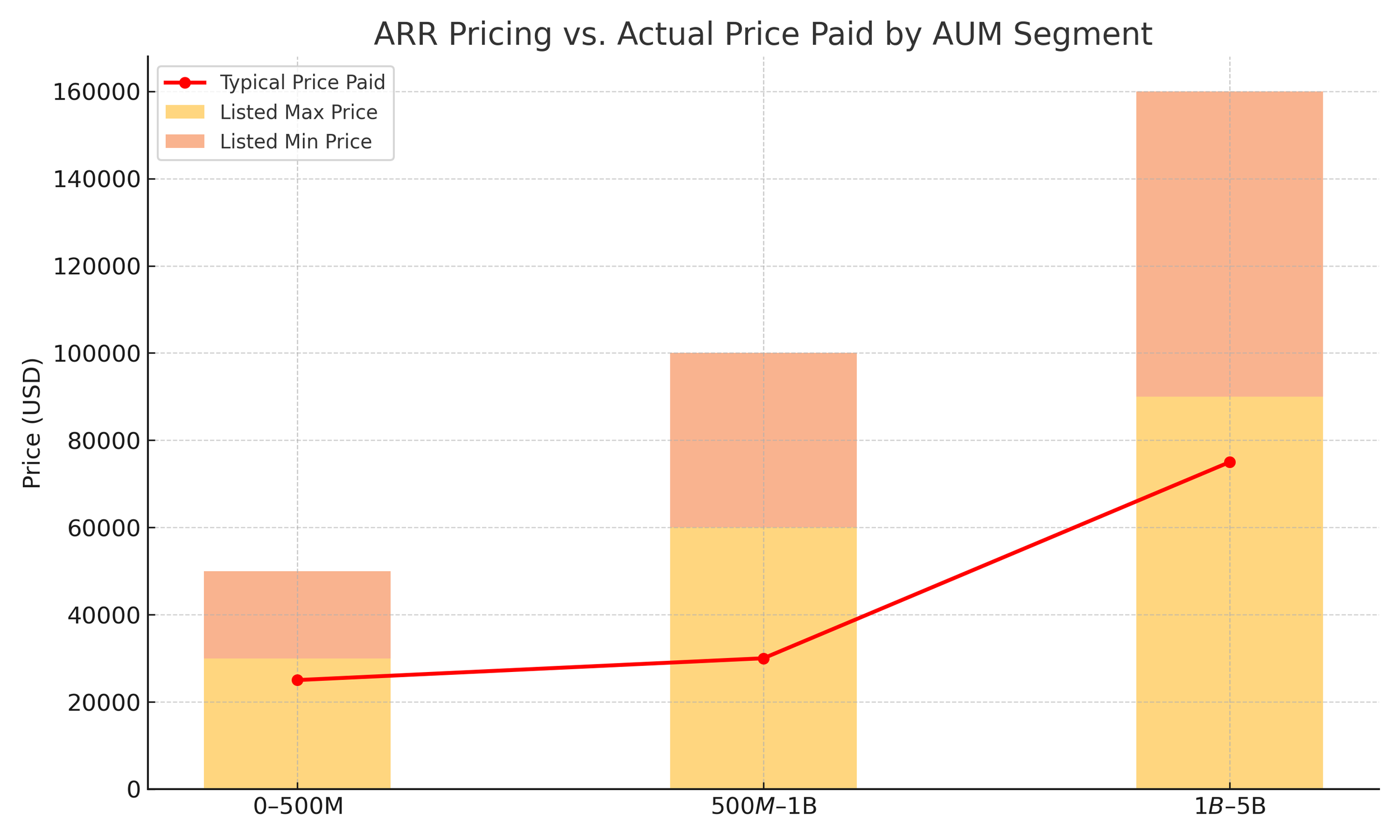

In practice, our mid-sized customers rarely paid what we quoted. Despite fees being set at $40K–$60K, most closed around $30K, right back where smaller clients were priced. That downward pressure became a recurring theme:

Don’t Let Pricing Become Passive

Disruptive companies don’t just build better products. They price like they believe in them and invite the market to believe too. It tells your customers who you are, how you think, and whether you're worth the bet. If your pricing looks like your competitor’s and you’re not the category leader, it’s probably not strategic. It’s safe. And safe doesn’t scale.

Sales leaders should always look at tangible outcomes when thinking about pricing. In our scenario, the flat fee for the entire product made it easy for a buyer to compare us feature for feature to other regional players. Had we (sales & product) collaborated further on outcomes like quarterly investor reports run, and data uploads, the real jobs of the software, it may have been easier for customers to tie the value to immediate wins and lock on to the differentiators. We knew our customers loved our reporting function, and therefore we should have built pricing around that platform, shifting the buyers level view across all vendors.

Especially when entering new markets or launching differentiated features, pricing must evolve. It should adapt to usage, customer maturity, and new data. It should invite experimentation, not fear.